By David Mullen

Baseball has reached a point of no return. Hitters are heading to the plate, swinging mightily and returning to the dugout with no return.

So far in 2021, 18 teams have batting averages of .237 or less. In 2015, no teams hit below .240. The Texas Rangers are hitting .226. The Milwaukee Brewers are hitting .212, yet, as of June 16, they are tied for first place in the NL Central. Today’s professional baseball players appear to be strong proponents of wind power.

Players have fallen in love with a “long ball or bust” mentality and it is killing the game. Blasts and bat flips are in. Bunts and sacrifice flies are out. Applying strategy just isn’t sexy enough to make “SportsCenter.”

Home runs make great video clips. On the MLB-sponsored website baseballsavant.com, hitters are now measured by metrics like Sweet Spot Percentage, Barrels, Exit Velocity, Batted Ball Distance, Projected Home Run Distance, Launch Angle and Batted Ball Events. What in the “wide, wide world of sports” is a “Batted Ball Event?” A Halloween Party?

In 1998, the second of his two AL MVP seasons, Rangers right fielder Juan Gonzalez had 606 at bats, hit .318 with 45 home runs and 157 RBIs. He had 50 doubles. His OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) was .997. The Rangers won the AL West.

This season, a leading candidate for AL MVP is Los Angeles Angels video sensation Shohei Ohtani. His measure of success looks much different. He has hit a ball with a 119 MPH exit velocity, has a sweet spot percentage of 35.3, a barrel percentage of 14 and has hit a 470-foot home run.

The Angels have a losing record and are a distance third place in the AL West. But Othani and others have a lot of hits on YouTube, if not on the field.

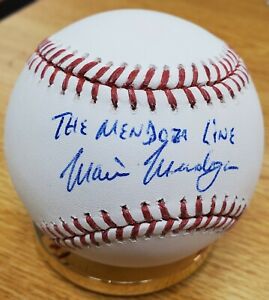

The infamous “Mendoza Line,” named after light hitting infielder Mario Mendoza, was a hypothetical stat line. Back in the Stone Ages before the Internet, the local newspaper’s Sunday sports section featured all Major League players’ batting averages. If you were hitting below the Mendoza Line, around .200, you were having a bad year.

Mendoza finished his nine-year playing career with a .215 batting average. This season, there are 14 everyday players that have appeared in at least 48 games hitting below .215.

This all leads to baseball rewarding players with flair, not players that can hit flares. MLB knows they have a problem with too little hitting and spent months doing interviews, analysis and tracking studies and have finally identified the culprit preventing players from putting a ball in play.

It’s the pitcher.

MLB has said nothing about the player’s lack of plate discipline, umpires creating their own strike zone to fuel their huge egos, the desire to be featured in the “MLB The Show 22” video game or the plethora of ridiculous measurements like ball velocity off of the bat or launch angle.

Baseball has said that hitting is difficult because of the pitcher. I could have told them that.

On June 15, responding to strikeouts galore and the lowest team batting averages in more than 50 years, baseball commissioner Rob Manfred came out with a scathing indictment that pitchers have an unfair advantage. In a release, Manfred said foreign substances, like pine tar and sunscreen, give pitchers better control of throwing a slick baseball. He said that starting on Monday, June 21, major and minor league umpires will start regular checks of all pitchers.

“After an extensive process of repeated warnings without effect, gathering information from current and former players and others across the sport, two months of comprehensive data collection, listening to our fans and thoughtful deliberation, I have determined that new enforcement of foreign substances is needed to level the playing field,” Manfred said in a statement.

“I understand there’s a history of foreign substances being used on the ball, but what we are seeing today is objectively far different, with much tackier substances being used more frequently than ever before. It has become clear that the use of foreign substance has generally morphed from trying to get a better grip on the ball into something else — an unfair competitive advantage that is creating a lack of action and an uneven playing field.

“Many baseballs collected have had dark, amber-colored markings that are sticky to the touch. MLB recently completed extensive testing, including testing by third party researchers, to determine whether the use of foreign substances has a material impact on performance. That research concluded foreign substances significantly increase the spin rate and movement of the baseball, providing pitchers who use these substances with an unfair competitive advantage over hitters and pitchers who do not use foreign substances, and results in less action on the field.”

Pitchers will be ejected and suspended for 10 games with pay for using illegal foreign substances to doctor baseballs. In essence, they will be given a paid vacation. They can take their sunscreen to the beach where it belongs.

Manfred tied offensive inefficiency to a sticky substance, rather than addressing a sticky situation. He has helped create an environment where baseball fundamentals are eschewed for individual noteworthiness. Scratching out a run is not important anymore. Why promote the nuances of baseball when you can reach a young audience with video of a Herculean swing and a two-story bat toss?

Ted Williams, the greatest hitter of all time, said, “Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of 10 and be considered a good performer.” Today, if you hit two times out of 10 — if it goes a long way and has a “velo” of 115 MPH — you can start in the Major Leagues.

Baseball has given bad hitters the ultimate out. “Don’t worry kid. If you can’t hit, it’s the pitchers fault.”

In Navojoa, Mexico, a 70-year-old retired major leaguer is teaching his grandchildren and other local kids how to hit. The man with the smile on his face is Mario Mendoza.