By Dr. Beth Leermakers

As we celebrate Independence Day, let’s honor the military horses who helped us achieve freedom from British rule. In this age of instant communication and delivery, it’s hard to imagine a time when people relied on 4-legged horsepower. We may think of horses charging into battle, but during the American Revolution they were more widely used for other purposes.

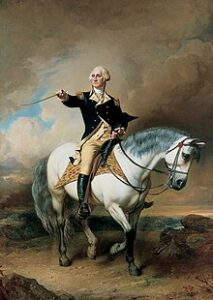

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

Roles of Military Horses

Communication (messenger carriers). On April 18, 1775, a borrowed horse (of unknown name and breed) carried Paul Revere on his famous Midnight Ride from Charlestown, Mass. to Lincoln, Mass. Revere sent the alarm that British soldiers were planning to remove arms and supplies from the town of Concord, a major supply area. As Revere rode through towns along his route, more alarm riders rode out, signal guns fired, and church bells rang, all warning people of the coming threat. Revere didn’t say, “The British are coming”— a statement that would have confused the locals, who still considered themselves British. Instead, Revere said, “the Regulars are coming.” Revere’s “message tree” worked well. By the time the British arrived, the men of Concord, Acton, Medford and Lincoln were ready for them. On April 19, the Battle of Lexington Green between Massachusetts militia men and British redcoats kicked off the Revolutionary War.

Transportation/Workhorses. Horses did the heavy lifting, moving weapons and supplies. Horses pulled cannons, wagons and carts and hauled baggage on their backs. The 6-pounder cannons weighed as much as 1750 pounds! Horses carried supplies, equipment and wounded soldiers, allowing troops to maintain their fighting strength. On one infamous night, horses were hauled instead of haulers. On December 25, 1776, when Washington moved his troops (2400 soldiers, 18 cannons, and 50 horses) across the icy, 300-foot-wide Delaware River, the horses and artillery were transported on large, flat-bottomed ferries.

Front line communication. Strong, fast horses carried dispatch riders who delivered messages and orders between commanders and troops on the front lines. Horses enabled timely and accurate communication on the chaotic battlefield.

Cavalry. There are three types of mounted commands:

Heavy cavalry (cuirassiers). These soldiers wore armor and were used primarily for shock effect.

Light cavalry (hussars). Hussars (people) primarily engaged in reconnaissance, screening and liaison missions.

Dragoons. Mounted infantry typically dismounted their horses to fight. War horses were bred to be calm. In the 18th century, some horses were acclimated to live fire by standing before a line of cannons. The traditional cavalryman in the U.S. Army is the light dragoon — a soldier trained and equipped to fight mounted or dismounted, perform screening and reconnaissance and act as a scout. Armed with sabers, pistols and occasionally a carbine musket, these light cavalrymen excelled at reconnaissance and screening infantry movements, but they could also charge onto the battlefield at critical moments to create terror in the enemy ranks and pursue a broken opposing force.

Because General George Washington didn’t realize the value of cavalry regiments, and the Continental Congress was put off by the cost to equip them, there were very few mounted units at the beginning of the war. Washington’s experience with the Light Horse of Philadelphia (a mounted-militia command) convinced him that horses were valuable. After Washington recommended to Congress that mounted units be established in the Continental Army, a regiment of light dragoons was formed on December 12, 1776. Congress authorized 3,000 light dragoons on December 27, 1776. During the winter of 1777, the Army organized four regiments, but they didn’t reach their full potential due to difficulty recruiting men and procuring horses and arms.

General Washington’s trusty steed. Dubbed by Thomas Jefferson as “the best horseman of his age,” George Washington often rode his favorite horse, Nelson (who was a gift from Thomas Nelson), during the war. Washington preferred to ride Nelson, who was less skittish during cannon fire and the startling battle noises, instead of his other horse, Blueskin. Washington rode Nelson on the day the British army surrendered at Yorktown in 1781.

As you’re watching the fireworks (please keep your pets inside and safe!), please remember the human and equine solders who made our freedom possible.

Happy 4th of July!!