By David Mullen

In the nearly 150 years of professional baseball, there has been no greater player than Willie Mays, who died on June 18 at age 93. The baseball world lost a legend. I lost a hero.

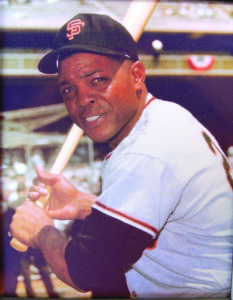

Photo courtesy of the

McCovey Chronicles, MLB.com

Known as “The Say Hey Kid,” Mays had a national following — without the benefit of 24-hour sports networks and social media clips — because of the stories of his remarkable baseball feats. At the time, baseball was far and away “America’s Game” and Mays was worshiped first in New York and later in San Francisco, where the Giants moved to in 1958.

The San Francisco Bay Area was in awe of Mays’ talent and grace. Growing up in Oakland in the 1960s, I was one of those idolizing Mays. Back then, a boy played baseball and then read about baseball and then listened to baseball on the radio, dreaming that he could someday play like Willie. The Giants also had Hall of Famer Willie McCovey, but there was only one Willie.

We tried to make basket catches like Willie. We championed his greatness. This New York Yankee Mickey Mantle guy was some East Coast outlier to a nine-year-old on the West Coast. Old-timers told us we should have seen Joe DiMaggio or Ted Williams play. Why? We had Willie.

All the money I earned by cutting lawns went to buy baseball cards and 9V transistor radio batteries. Baseball was rarely seen on TV. Baseball was viewed on the radio.

The Giants’ games were colorfully broadcast by the award-winning team of Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons. When Mays hit a home run, Hodges would yell, “Bye, Bye Baby!” or Simmons would scream, “Way back. Way back. Way back. Tell it goodbye!” I imagined what it must have been like to have been at the game.

My dad took me to my first baseball game in 1965. We went to blustery Candlestick Park in San Francisco to see Willie Mays. He hit a home run. I know because my dad kept score and I still have the program.

Mays’ career began in the Negro Leagues. The Westfield, Ala. native began playing for Birmingham Black Barons on weekends. He went to high school during the week.

In 1951, Mays was called up to the major leagues in May by the New York Giants. He started out 0 for 12. In his 13th at bat, Mays homered off Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. He would win Rookie of the Year and play a key role in the Giants late run for the pennant. He was in the on-deck circle when Bobby Thompson ended the Brooklyn Dodgers’ season with the “Shot Heard ‘Round The World.” Mays was the last player alive who played in that game.

Mays served in the military in 1952 and 1953. Had he played during those years, he certainly would have improved his lifetime stats of a .301 batting average, 3,293 hits, 660 home runs and 1,909 RBIs. When he returned for the 1954 season, Mays won his first of two NL MVPs and led the Giants to the World Series.

In the 1954 World Series, Cleveland Indians 1B Vic Wertz hit a fly ball to the deepest part of the expansive Polo Grounds. Mays sprinted, with his back to the infield, and made a ridiculous over the shoulder grab simply known in baseball circles as “The Catch.” The Giants swept the Indians.

Mays got off to a slow start in the 1961 season, totaling two home runs and six RBI in 15 games. In his 16th game, on April 30, 1961, Mays hit four home runs and had eight RBIs in a 14-4 win over the Milwaukee Braves, becoming the ninth player in big league history to hit four home runs in one game.

Babe Ruth, Henry Aaron and Barry Bonds never hit four home runs in one game.

With Mays, the San Francisco Giants were a great team in the 1960s, but never great enough. From 1962 to 1970, the Giants never won less than 88 games but finished second five times and only played in one World Series.

Pitchers dominated hitters in the 1960s. In 1965, Mays regularly faced Los Angeles pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, St. Louis Cardinals ace Bob Gibson and Philadelphia Phillies veteran Jim Bunning. All four pitchers are in the Hall of Fame. Mays hit .302 with 52 HR and 112 RBIs and won the NL MVP.

Mays finished his career with the New York Mets. His last career hit was in Game 2 of the 1973 World Series off Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers of the Oakland A’s. Mays appeared in 24 All Star games and won 12 Gold Gloves. He was the original five-tool player (run, field, throw, hit for average and hit for power) and is the only player in MLB history to hit .300 for his career with 300 homers and 300 steals.

A valuable lesson for today’s professional athlete, Mays was committed to marketing the game, not marketing himself. Although his career hitting totals are beyond reproach, what set Mays apart was his defensive play. “I like defensing,” Mays said. He often said that he could make the hard play look easy and the easy play look hard, hoping that fans would “see something they liked and come out to the ballpark tomorrow.”

“You went to the ballpark to see Babe Ruth hit,” the very quotable Reggie Jackson said. “You went to see Willie Mays do everything.” And he could do everything. Just ask a kid who grew up with Willie Mays as a hero.