By David Mullen

On January 25, 1987, in Pasadena, Calif., the NFL could not have requested better conditions. It was a picture perfect 76 degrees at the Rose Bowl Stadium, as the New York Giants and Denver Broncos lined up for the opening kickoff in Super Bowl XXII.

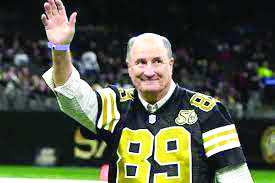

Photos courtesy of the New Orleans Saints

Neil Diamond had just concluded the National Anthem. I was one of 101,063 attendees at the game and had the great fortune of sitting in a 50-yard line seat. Back then, attending a Super Bowl was possible without breaking into Fort Knox. Sitting next to me was a 6-foot, 4-inch former NFL tight end named Kent Kramer. Being 5-foot, 7-inches tall, I was just happy he was sitting next to me, not in front of me.

Kramer told me he lived in McKinney and owned a sports marketing company specializing in incentive travel. He was an avid golfer — a passion we shared — and he promised we would stay in touch. Kramer never returned to his seat in the second half of the Giants 39-20 victory, and I was sure I would never see him again.

Weeks later, Kramer called me at my Dallas office. Little did I know that our chance meeting at the Super Bowl would initiate a deep friendship that lasted nearly four decades.

Born in Los Angeles in 1944, Kramer was an All-CIF (California Interscholastic Federation) football player and had a stellar career at the University of Minnesota. He played in the NFL for eight seasons with the San Francisco 49ers, New Orleans Saints, Minnesota Vikings and the Philadelphia Eagles, and was on the Vikings team that lost to the underdog Kansas City Chiefs in Super Bowl IV. A knee injury shortened his playing career.

My friend, the late Monte Stickles, was the starting tight end for the 49ers during Kramer’s rookie season. “I took Kramer under my wing,” Stickles told me, when I told him I had become friends with Kramer.

“Stickles told me the opposite of what I was supposed to do,” Kramer would later tell me. “The coaches would yell at me.” When I told Stickles, he laughed and said, “I was trying to keep my job.”

Kramer was the antithesis of a stereotypical big dumb jock. As a player, he was a team union rep and later remained very active in the NFL Alumni. He was reserved, thoughtful and rarely raised his voice. I was more likely to rant while Kramer kept the peace. Kramer married his high school sweetheart, Kendra, and they recently celebrated their 60th anniversary. He was a devoted husband, father and grandfather.

In 1992, Kramer became co-owner of the Arena Football League Dallas Texans. He called me one day, and in his soft spoken yet convincing voice said: “Listen. I need you to do me a favor. I need you to buy season tickets to the Texans.” “No problem,” I said, quasi-familiar with the rules of Arena Football. “As long as they are on the 25.”

We took many trips together and were always roommates. It was like the biggest lineman on the football team bunking with the place kicker. We played Pine Valley in New Jersey. We went to the Ryder Cup in Ireland. We played golf throughout Alberta, Canada and sat at the base of the Athabasca Glacier. Kramer was instrumental in the development of a new campus football stadium for his alma mater Minnesota Golden Gophers. We went together to the first game played at the new facility.

He had unparalleled access to the Masters at Augusta National Golf Club. He was so well connected that he could gather enough of the coveted Masters badges to entertain clients and friends. He invited me to join him at Augusta one year. I guess he needed a roommate.

On our very first golf outing in Scotland, we began at Prestwick Golf Club near the town of Ayr. Hole No. 1 — Railway — is one of the most famous opening holes in golf. A narrow fairway is framed by gorse and heather on the left and a wall protecting a commuter train platform on the right. An arrent tee shot could send train passengers running for cover. Luckily, I overcame my nervousness and kept the ball in play. Kramer and I would begin the first of multiple golf trips to the U.K. The stories are too many to tell.

We befriended a group of caddies in Troon, Scotland. For years, Kramer and I would contact them prior to our trips, and they would caddy for us. Tiger Woods had Fluff (caddy Mike Cowen). Phil Mickelson had Bones (Jim Mackay). Kramer had Waddie. I had Jimmy Main.

One day at a pub in Troon, the caddies joined us for a pint. “Aye, Karrr-aim-err. Aye, Wee Davey,” Main said with a thick brogue. Kramer always paused before he laughed like he was processing information. I had never heard Kramer laugh so hard, and from that point on, whenever I picked up the phone and heard “Wee Davey” in a poorly executed Scottish accent, I knew it was Kramer.

It wasn’t until Kramer and I went to Honolulu to the NFL Pro Bowl that I learned of his deep connection to Hawaii. His father and three brothers were born there, and his mother lived there for decades. He was so proud of his adopted homeland. We visited his favorite restaurants and met his island friends.

After a perfect beginning in 1987, the story has an imperfect ending. Kramer died peacefully in his sleep on February 21 at his McKinney home. He was 79. Foregoing the traditional suit, Kramer was buried in a Hawaiian shirt. The title of his obituary read, “Aloha and A hui hou!” Goodbye, and until we meet again.