By David Mullen

Hall of Fame baseball players like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Reggie Jackson, Rickey Henderson and others would tell you how great they were. So would Hall wannabes Pete Rose, Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens.

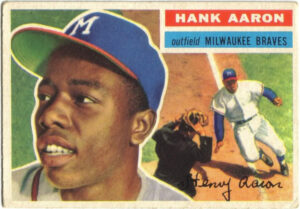

Photo courtesy of al.com

Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron was deafening with his silence. He let his bat and skill on the field and demeanor off the field do all of the talking.

“My motto was always to keep swinging,” Aaron said. “Whether I was in a slump or feeling badly or having trouble off the field, the only thing to do was keep swinging.”

Having played 25 seasons for the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and the Milwaukee Brewers, Aaron died quietly on January 22 at the age of 86. He was not only one of the top players in baseball history, but he was also one of the humblest.

When I was a kid, baseball had two “superstars” before the phrase had even been coined. They were Willie Mays and Aaron. I saw Mickey Mantle play just once, when age and a recurring knee injury hampered him from being the player we had heard about. Living in the San Francisco area, it was logical to pick the Giants centerfielder Mays, although I was a huge fan of Giants Hall of Fame first baseman Willie McCovey. We shared the same birthday.

Games were rarely on TV, and ESPN was a decade away from running its first highlight reel. Plus, I could see Mays play live and often did, until the A’s moved from Kansas City to Oakland, and I had my team.

We learned about players through Topps baseball cards, the Sunday sports section containing every Major League player’s stat line and The Sporting News — nicknamed “The Bible of Baseball” — which caused a sprint to the mailbox on the day of arrival. We all knew that Aaron was great, but Atlanta might as well have been in another country. He was not hated; he was respected. “OK, we lost that one. But it was ‘Hammerin’ Hank’ who beat us.” No one in my neighborhood said that about Rose.

Aaron finished his career among the all-time greats in nearly every batting category. In these times of flawed records, when both baseballs and baseball players are (allegedly) juiced, Aaron played with integrity and still ranks second all-time in home runs (755), third in career hits (3,771), fourth in runs scored (2,174), first in RBIs (2,297) and in total bases (6,856). He made 25 All-Star teams.

In 1982, Aaron became a first ballot Baseball Hall of Famer, receiving 406 of the 415 votes. Accustomed to racism in baseball — often magnified in Hall of Fame voting — nine baseball writers did not even include Aaron on their ballot. Nine! The all-time home run leader! Aaron shrugged off his slight, just proud to be enshrined.

Aaron got his start in professional baseball with the unfortunately named Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League in 1951. While playing in front of segregated crowds in the Braves farm system before his call-up in 1954, Aaron cited one of many early experiences to Hall of Fame baseball writer Peter Gammons.

He told Gammons that after he finished eating at a diner in Washington D.C. with teammate Felix Mantilla from Puerto Rico, he heard a din coming from the kitchen. Rather than wash and reuse them, the staff was breaking the plates that Aaron and Mantilla had eaten from.

His career was as steady as any in baseball history, which is the main reason he won only one MVP award (1957). But he captivated America in 1974 and did so with grace and aplomb.

Baseball’s sacred and, seemingly, unbreakable career home run record of 714 held by Ruth was within Aaron’s reach. Despite unthinkable racial slurs via phone, letters and vociferous ticket holders (they can’t be referred to as fans), in the fourth inning of a night game on April 8, 1974, Aaron hit a high 1-0 fastball off Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Al Downing into the left centerfield bullpen at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium for No. 715. The ball was caught by teammate and former Texas Rangers pitching coach Tom House, who sprinted to the infield and gave the ball to Aaron.

Aaron kept the hate mail full of death threats and “N-bombs,” and said he did it “to remind myself that we are not that far removed from when I was chasing the record. If you think that, you are fooling yourself. A lot of things have happened in this country, but we have so far to go. There’s not a whole lot that has changed. The bigger difference is back then they had hoods. Now they have neckties and starched shirts.”

In a rare moment of humility, boxing great Muhammad Ali once called Aaron, “The only man I idolize more than myself.”

When Aaron retired, he continued to advocate civil rights issues and youth development through his Chasing the Dream Foundation without fanfare.

He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush. And, of course, he also played golf. “It took me 17 years to get 3,000 hits in baseball,” Aaron said. “I did it in one afternoon on the golf course.”

On January 18, MLB mourned the loss of Hall of Fame pitcher Don Sutton, who gave up three home runs to Aaron. Sutton’s former Dodgers teammate, the late Hall of Famer Don Drysdale, gave up 17, the most home runs any pitcher yielded to Aaron.

“The only sensible thing — if you couldn’t get the manager to let you skip a turn against him — was to mix the pitches and keep the ball low,” Drysdale once said about pitching to Aaron. “And if you were pitching to spots, it was important to miss bad. If you missed good and the ball got in his power zone, sometimes you were glad it went out of the park and was not banged up the middle.”

Henry Aaron, a native of Mobile, Ala., brought incredible talent to a game engulfed in racial prejudice. Like Aaron did in 1974, records will be broken. But no one will break the legacy of strength and courage Aaron possessed on and off the field. He just kept swinging.