By David Mullen

I learned professional football from John Madden, who passed away on December 28 at 85 years old. I didn’t learn from listening to his broadcasts, watching him draw lines on a TV screen or playing a video game. I learned from him as head coach of the Oakland Raiders, as so did many others who grew up in Oakland in the 1970s.

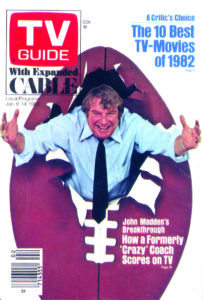

The tributes that continue to pour in over Madden’s death are well deserved. Any level of professional football fan knew of Madden. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said, “He was football.” Most saw Madden as an expert analyst, likable advertising promoter or video game pioneer. I saw him as someone completely different.

The “Silver and Black” Raiders epitomized Oakland. Silver isn’t as precious as gold and only bad guys wore black hats. Oakland was a blue collar town, located only eight miles but light years away from chic and trendy San Francisco. We didn’t like all the attention San Francisco received.

Photo courtesy of Flickr

They drank chardonnay, ate fancy chef-prepared meals off fine China and cycled on designer 10-speeds in “The City.” We drank shots of whiskey, ate barbeque ribs off paper plates, and only the Hell’s Angels cycled in “The Town.”

The Raiders were part of the Oakland fabric. Fullback Hewritt Dixon came over to our house. Hall of Fame tackle Art Shell taught me wood shop as a substitute teacher. Gene Upshaw and Clem Daniels had bars and Charlie Smith and Hall of Famer Willie Brown owned liquor stores. My older cousins lived in the same apartment complex with Hall of Famers Ken Stabler and Dave Casper.

Coach Madden was blue collar, too. He grew up across San Francisco Bay in Daly City, a place on the San Francisco border that was a series of copycat houses built after World War II. To understand how Madden became a worldwide sensation, one must understand how he earned his fame.

Coach Madden famously said, “The road to Easy Street goes through the sewer.” It was his way of saying “it takes years of hard work to become an overnight sensation.” We appreciated his values.

Coach Madden worked hard and looked different. His hair was always unkept. His field pass hung from a belt loop on his polyester slacks. He wore a tie with a short-sleeved shirt. When he yelled at the officials, he was yelling for us. He knew the game, could find ways to stop offenses and exploit defenses and earned the respect of his players. His rules were, “Players had to be on time, pay attention and play like Hell when I told them to.” That worked for us in Oakland.

His favorite players were lineman, the guys who were “in the trenches” and unheralded for their effort. Madden was a lineman in high school and college. A knee injury kept him from playing offensive line in the NFL. My dad was center on the football team at St. Elizabeth’s High School in Oakland. When their quarterback Rudy Solari went on to Hollywood to become an actor, he landed a role in the ABC military series “Garrison’s Gorillas.” When Solari appeared on screen, my dad would say, “That guy had his hands under my butt” and laugh, even though he said it every week. My dad was a little like Coach Madden.

Oakland always had an inferiority complex with San Francisco. But if the Raiders won, it didn’t matter. And Coach Madden won. He has the highest winning percentage of any coach in NFL history with at least 100 wins. While Madden led Oakland from 1969-79 — the only team he ever coached — the cross-bay rival 49ers went through six different coaches.

I grew up the oldest of four children in a family that could not afford Raiders’ season tickets. But many relations and family friends had them, and since we lived minutes from the Oakland Coliseum — home of the Raiders — an extra ticket frequently came my way. I sat by the phone on many Sunday mornings waiting for the phone to ring, which never had to ring twice.

Despite sellouts, home games were not televised locally by NFL mandate. For a big game, my dad would drive the family to a friend’s home in Sacramento or Monterey to watch the game on their local NBC affiliate. We would drive for hours to see a game being played down the street from our house.

In 1975, I was invited to interview Hall of Fame punter Ray Guy in the Raiders locker room after a practice. I was editor of the Skyline Oracle, the school newspaper at one of Oakland’s six public high schools. The school district didn’t even ask if I was a Raiders fan. Everyone in Oakland was a Raiders fan.

I had seen Coach Madden many times on the sidelines, but never in his own locker room. I thought he might throw me out, but his mind appeared to be on the game ahead. I remember seeing Brown and future Hall of Famer Ted Hendricks coming out of the shower snapping towels at each other as if they were in high school, too.

One of my proudest moments was watching Coach Madden hold the game ball in the air after winning Super Bowl XV at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. The Raiders had just annihilated the Minnesota Vikings. The world had heard of Oakland now, and John Madden had just put us on the map. The 49ers had not yet won a Super Bowl. For once, San Francisco couldn’t steal Oakland’s thunder.

Oakland has changed. Built as a convenient way to travel, Interstate 580 serves as a great divide. The hill dwellers on one side of the freeway are wealthy while the dirt-poor flatlanders on the other side live with gang warfare, drugs and deplorable crime. There is no in between. Blue collar families have moved out.

Madden will be remembered by most for smashing through walls on Miller Lite ads, making sure that we knew that Tinactin is “Tough Actin” and that “Ace is the place,” his “booming” broadcasting style or insisting an animated football game be authentic before he would put his name on it. But I’ll remember Coach Madden for his football acumen, his blue collar ethic and how he gave my much-maligned hometown a personality of our very own.